Musical Director of the Society from 1937 until 1988

(From ‘Tributes and Memories’, in The Recorder Magazine, Summer 2006 edited by Andrew Mayes)

There can be few in the recorder world who do not know the name Edgar Hunt; many recorder players knew him and he in turn knew many recorder players. Yet perhaps few knew him very well, not because he was unapproachable, indeed he was quite the opposite. Nevertheless, his natural modesty prevented him from giving away much about his remarkable contribution to the recorder and its music.

His achievements were many: co-founder of the SRP, founding professor of the Early Music Department at Trinity College London, Honorary Secretary and later President of the Galpin Society and co-founder and for forty-one years chairman of the Recorder in Education Summer School. His invaluable work at Schott’s, both in editing music and ensuring the supply of inexpensive but good quality recorders for educational use was yet another area of influence. If one adds to these the contribution of one of the major books on the recorder, his editorship of The Recorder Magazine (for sixteen years) and the founding (in 1973) and editing of Harpsichord and Fortepiano magazine, it is no surprise that he was the recipient, in 1997, of the American Recorder Society Distinguished Achievement Award.

Edgar’s was a quite extraordinary contribution to the recorder, but bare facts alone provide only a part of the picture of the very special man he was. Many people have particular memories of him and wished to share them in tribute. One is put in mind of the pictures creatively made up of many small images that when viewed overall form a detailed and complete image. There can be no better way to provide a picture of Edgar than that made up of the memories of those whose lives he influenced. We thank them for their recollections and tributes that appear below.

I began studying with Edgar Hunt at Trinity College of Music in about 1963 and successfully passed the LTCL diploma in 1964. Right from the beginning Edgar was the guiding light in my career. His infinite patience, generosity and good humour, were legendary. He had such a considerable store of knowledge and such a desire to share it with others. I can truthfully say that nearly everything I know comes from, or has its roots in what he taught me.

He gave me a great deal of sheet music – and even some (very precious) hand-made copies of extracts from Handel’s Acis and Galatea – dated 1929! He lent me instruments and introduced me to the viola da gamba. Thanks to his initiative I applied for and won a British Council Scholarship to study in the Netherlands with Kees Otten – thus becoming the first English student to do so. Thanks to Edgar I went to recorder courses in France and Holland, soon becoming an instructor. I also played with him in a number of concerts in London, Bristol, Toulouse and Lorient. On one occasion I was privileged to play his famous Bressan recorder while he played the traverso in a performance of the trio-sonata by Quantz.

He was an excellent musician playing several instruments: transverse flute, traverso, recorder, cello and viola da gamba. He was also a very competent conductor. In spite of his great knowledge and versatility he never sought the limelight. One had the impression that his one desire was to serve the music he loved and to make it available to as many people as possible. He was also interested in finding adaptations to instruments to enable handicapped people to play them.

He was a very refined gentleman – he had beautiful handwriting and was most considerate of others. He enjoyed good food and good wine and was always ready for a joke. I have memories of riotous evenings “after hours” at Roehampton and on other courses. I remained in contact with him right up until his death and will sorely miss him.

Beverly Barbey

Reading again the many tributes to Edgar in the March 1991 Recorder Magazine, I am struck, as always, by the way certain phrases – ‘unstinting of his time and knowledge’, ‘encyclopaedic knowledge’, ‘gentle and ever helpful’, ‘modest and self-effacing’ – crop up in varying forms, time after time.

Fifteen years on these epithets still paint a vivid picture of Edgar as I knew him, and to whom I was, and am, so grateful for his quiet encouragement, first when a mere summer school student and later as a fellow tutor.

His is a fascinating story and, as I marvel at his determined efforts to re-establish and further develop the role of the recorder, I often wonder if he has yet received the recognition he deserves. Without him, all that we now so happily accept as an important part of our lives might never have come to pass. Is it then too late to make amends by marking his achievements in some permanent way?

Brian Bonsor

I received the sad news about the death of Edgar Hunt from Michele Henry, with whom I am in contact again after 35 years of silence. Our life and work had gone so far apart, but the death of her father Jean Henry brought us back together.

Early Music Courses organised by the UFOLEA with our masters Henry, Hunt, Le Borgne, Denis, Temprement, Dolmetsch, Otten, Brüggen, …. have allowed many French teachers-students to study the recorder and its pedagogical applications. In parallel, they also discovered early and baroque music, the practice of amateur chamber music, and often … found there their life companion (wife or husband). That’s how I met Denise, since then my wife. With close teacher friends we decided to form our medieval music ensemble “Les Croque-Notes” that worked, researched and performed in Normandy, and “I:Academie Baroque”, an ensemble that worked exclusively on facsimiles and copies of original instruments.

Edgar Hunt played a part in those years of formation and discovery. Elizabethan music, John Dowland, William Byrd, Thomas Morley held no secret for him. In consort music, being tall, with big fingers and able to play with seven keys and substitution fingerings, I often played the great bass in C. I had therefore the privileged to observe the master and to feel harmonies and structures.

Yes, Edgar Hunt was a true gentlemen who mastered the French language with all its refinement and subtleties, more that he dared admit. He had a talent of finding a way to win over a pupil’s weakness and rebuild their positive qualities. He never put one in difficulty and we never left his lessons or ensembles without having progressed. All his old disciples will retain a memory of a friendly, careful, distinguished interpreter (you immediately recognised his charming way of playing among thousand of others – it was so elegant), capable of bowing to his public during applause in a very particular way of folding in two parts!

Edgar will ever accompany us when playing Byrd’s Sellenger’s Round, Morley’s Come lovers follow me and Adieu ma Dame et ma Maitresse by Henry VIII. Yet no more will we play together the 4th Brandenburg with 2 recorders in F at the Chapelle du Prytanée at la Flèche.

We are very sad to have lost in such a short time two pillars of our pedagogical and amateur music-making family. Edgar Hunt and Jean Henry were two men of great value and so attentive of their friends. The Norman Baroque-like countryside is in mourning.

Francois and Denise Gosselin

During the last 29 years I kept in touch with Edgar. In January 1978 he was in charge of a summer course in my country Chile that lasted two weeks. On that occasion we had people from Buenos Aires and Colombia and, as he was well known, people from North and South of the country, nearly 200 musicians. He was the inspiration for many young recorder players. I came to London in 1980 to study with him at Trinity College of Music. He was really a great musician and a wonderful friend.

Maria Harjani

I met Edgar Hunt first in 1997 while staying in London for the finals of the Moeck/SRP Solo Recorder Competition. I had previously arranged to visit him at his daughter’s house in Ealing where he lived, and asked him to tell me all he knew about the history of the competition. At first he seemed rather unapproachable and I feared that my visit was inconvenient to him after all. But then he started talking. He seemed to have memorised the entire history of the English recorder scene and was very entertaining while relating it. He knew an answer to all my questions. We talked about his long association with Moeck-Verlag. My grandfather published two of his editions of English music in 1935 and 1937, one of which is still available. The afternoon flew by and I gained the impression that he had enjoyed it as much as I had. About three weeks later, I received a letter from him with more precise details and dates about what he had told me. His last sentence was: “I am so glad to have met you.” This really moved me because it was just the way I felt myself.

Sabine Hasse-Moeck

The first time I met Edgar Hunt was during my first visit to Great Britain at Roehampton, where I also met Carl Dolmetsch and Walter Bergman. The Recorder Society course was paradise: surrounded by lovely people, music in every room and every corner of this huge place. There were tea and cakes all the day, caring ladies making you feel at ease: a whole philosophy of creativity and making your own dreams come true through communion with other human beings.

Edgar was always there caring and tutoring where others failed. I could not speak of gentle Edgar without including loveable Elisabeth and swift Rosemary. I learnt from them the key of respect to culture. Rose Cottage was a wonderful blessing for me: no question, I became one of the family. I still hear the lovely sound of the cork popping out of the bottle on Sunday lunchtime, the only day of the week Edgar was allowed to forget his very busy life. After lunch we were taken somewhere special, laughing about nothing and everything. I learnt to remain still and not laugh or jump when Edgar entered his dark study-room full of serious books, to respect every pupil or guest visiting him as a very special honour and to queue for Royal Albert Hall concerts.

I became a mother and Elisabeth the godmother of my daughter Rachel. Later, Elisabeth became very ill and sadly I left Rose Cottage and went to Holland. Later I met Edgar again in Utrecht, walking along the “gracht” and in Nice along the “Promenade des Anglais”. By that time Edgar was very taken by an old hobby of his, photography.

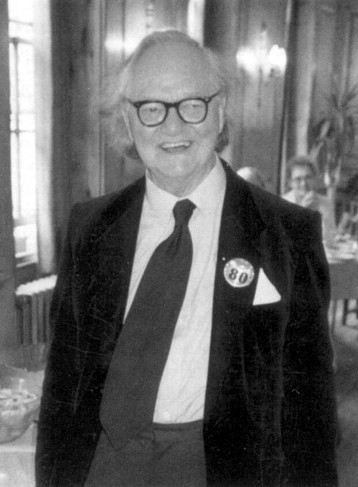

The last time I saw him was in London when he was eighty years old. Rosemary had organised a big party. Edgar, you never told me what you were hiding behind your mysterious Mona Lisa smile, always accompanied by a gentle hand on my shoulder saying every time “Well!” then no more. You really were a Gentleman, without hat and stick, not like Gaston Saux who always wore them!

Michele Henry

I have known Edgar Hunt since 1966 as a connoisseur and teacher of the recorder. He had a private collection of some exquisite instruments, especially a Bressan Alto, or treble, and a 4th flute, which he let me study, photograph and take measurements of. He was among the first to perform the 4t’ Brandenburg concerto on the recorder, with Carl Dolmetsch, and later with Frans Brüggen. When the planning for the Boston Early Music Festival & Exhibition started in 1978, he became a staunch supporter who visited every Festival since 1981, lived in our house, and became an adoptive grandfather to our children who delighted in his company. He was a wonderful storyteller about his life in music as a flutist, recorder player and teacher. Always a peacemaker, he saw to it that there was only one Society of Recorder players in England. Edgar was fluent in French and with his friend, M. Henry, he started recorder courses in Arras. He also was an advocate for inexpensive recorders for school children and made several trips to Germany, visiting manufacturers who could fill the demand.

We shared the concern about pitch standards suitable for the performance of early music. He was chairman of the Woodwind subcommittee for setting standards and establishing “English Fingerings”. He wrote more than forty letters to us, showing his appreciation and enjoyment of life during his visits, sharing ideas and news of important events.

Friedrich & Ingeborg von Heune

With the death of Edgar Hunt comes the end of an era. When I joined the Society of Recorder Players in 1973, Carl Dolmetsch, Edgar Hunt and Walter Bergmann were the heart of the SRP (ably assisted by the next generation of Brian Bonsor, Paul Clark, Dick Coles, Herbert Hersom, Sam Taylor and Theo Wyatt). Recorder players owe much to Edgar Hunt. Carl Dolmetsch and he had founded the SRP, where they were later joined by Freda Dinn and Walter Bergmann as musical directors, but Edgar perhaps above all others in the early days saw the potential of the recorder revival both in early music and in education. He was often the quiet working force behind the Society, the original Recorder Summer School and of course at Trinity College of Music. His small stature and quiet demeanour belied his ability to take control of a situation, his organisational skills and intellect. He was also skilled at dealing with very varied personalities and bringing diverse opinion together. He was an extremely kind and perceptive man, who looked for potential talent in all the musicians he met and did all he could to support and encourage it, as he did in the case of Walter Bergmann, when he arrived as a refugee in Britain in 1939. Although not a student of Edgar Hunt, I am very grateful for the encouragement he gave me over the years, initially in my twenties on the Recorder Summer School and later in encouraging me to write for the Recorder Magazine. It was to Edgar I turned to ask advice as to whether I should embark on a biography of Walter Bergmann and I received his support as well as letters in his beautiful handwriting promptly replying to any query I sent him. It was typical that after his ,retirement’ he looked for new challenges and although a private man in many ways, he delighted in becoming a grandfather late in life, which was apparent to all who met him.

Anne Martin

Edgar received the American Recorder Society Distinguished Achievement Award in 1997 during the Boston Early Music Festival. I have vivid memories of him, at the age of 87, standing on a chair right beside a full-glass wall on the 33rd floor of the Bay Tower, regaling those attending the reception for him with his personal recorder stories. At the time, I remember hoping I would be able to do that at 87 without becoming dizzy and toppling off the chair! I also remember, at my very first BEMF in 1995, when I had to stay over until Monday following to make sure that our exhibition booth materials were shipped back to the office, that I spent a free Sunday afternoon at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. As I walked through the front door, he was leaving, but turned around to escort me directly to the musical instrument collection. He said that he visited it every time he came to Boston -it struck me as something one would say about visiting old friends, the way he said it.

Gail Nickles

My first memory of Edgar goes back to before World War II. At the age of 16 I tried to contact him, as he had published several small books of recorder music and many editions of modern recorder works. At that time I did not succeed because of the wartime situation. Shortly after, Edgar was in Holland and our first meeting resulted in a life-long friendship. He invited me throughout our lives to many courses in England and France, where in Arras I also met Jean Henry. He also died last year and I must confess I feel very alone.

One special personal memory I have had for many years is of staying with Edgar on Rose Cottage Lane where he lived with Claude de Pussy, his cat. It was an enjoyable time and we talked about and listened to music, had dinner together and so on. I remember him as one of the most lovely and generous of people. I will never forget.

Kees Otten & Marina Klunder

I can’t say that I knew Edgar well, but I suspect few people did. About himself he was modest, almost self-effacing. But I seem to remember that he once told me he came from a family of musicians who, though primarily brass players, were encouraged to have a go at any instrument. Edgar inherited not only musicianship, but a high level of wide-ranging intellectual curiosity.

My memories of him personally are from odd occasions, always happy. A special one was in Newcastle upon Tyne when my wife and I, just married, occupied a tiny flat in the grand Leazes Terrace, where I was warden of a small postgraduate hostel. I had been organising an SRP Annual Concert and Edgar came to dinner as our first non-family guest. We spoke a lot about the concert, but Edgar’s main conversation was about his pupils, each one of whom he regarded as a personal lifetime friend – and a just cause for pride. I am sure that for him, as a professor, teaching was far more important than research, though he excelled at both.

Over the years Edgar and I had quite a number of `research exchanges’, mainly him helping me, and he was always generous in his help. When I was compiling an appendix about makes of recorder for the first edition of Recorder Technique (withdrawn for the second edition) Edgar gave up a lot of valuable time explaining to me the differences between a well-designed instrument and a poor one – a memorable occasion. His 1962 book was at the time ground-breaking, when recorders were hardly regarded as important enough for serious research; and recorder scholarship was then a desert, so he had few sources to draw upon. Nowadays, when both the status of the recorder and the rigour expected in recorder research have greatly advanced, it is wrong to judge Edgar’s academic achievements by changed standards.

Despite his sensitivity, so evident in his playing (especially of twentieth-century music), I remember Edgar as an equable, not a temperamental person. Always welcoming and approachable, I am sure he will be equally welcomed in celestial music making

Anthony Rowland-Jones

In my mind Edgar is inextricably linked with the down-line platform at Amersham train station. David Munrow had moved to nearby Chesham Bois from St Albans, and I stayed with him and his hospitable wife Gill on the many occasions when I performed or recorded with the enlarged Early Music Consort. Edgar’s return from his day job at Schott’s often coincided with our return from rehearsals, and we used to walk back together along the same route, he to his cosy “Rose Cottage” and we to an exhilarating (if tiring) evening of recorder duets and stimulating musical conversation with David. Getting off the train in his suit, briefcase in hand, Edgar merged imperceptibly into the hordes of bankers, accountants and lawyers that spewed out of carriages. But Edgar was special – an object of veneration even then, as I knew his influence on the history of the recorder and its repertoire since the instrument’s revival in the 1930s.

The recorder was the great love of David’s life, and despite the ever-expanding ripples of his musical activities, the recorder was always centre-stage. He wanted to start a recorder consort and enlisted Edgar to play the bass in it, which he did immaculately, and with his usual quiet efficiency. I recall a broadcast, produced by Basil Lam, of accompanied madrigals, directed by Christopher Bishop. We recorded it in Broadcasting House in 1970, with the London Madrigal Singers (James Bowman and the much-lamented Susan Longfield in glorious voice), the Jaye Consort of Viols and David’s recorder consort (Edgar pooping away happily on the base line). It was on the short lift back to the station, provided by Chris Bishop, that David persuaded him (then a senior EMI producer with a pronounced aversion to recorders) to take the Early Music Consort on board with EMI, and the rest is history. Edgar, as usual, was in at the start!

His depth of knowledge was immense, and it was never too much trouble to search out information, or send copy documents or music. He was particularly helpful to me in matters concerning the recorder compositions of Alan Rawsthorne, Walter Leigh and Ernst Meyer, earlier twentieth-century composers for our beloved instrument. He is quite irreplaceable – a modest, far-sighted, gentle, persuasive and delightful icon of the recorder fraternity.

John Turner

The recorder world owes a great debt to Edgar Hunt, and no one owes more than I. When, aged 17, I discovered music and the recorder simultaneously, it was Edgar’s book (constantly renewed from Buxton library!) which fed my enthusiasm with real knowledge. So, having decided I wanted to make it my career, it seemed natural to write to him for advice. The reply, by return of post and written in his elegant copper-plate hand, was instructive, supportive and warm – and as such, as I was to learn, characteristic of the man. When, self-taught, I auditioned for a place at Trinity College, he overlooked my colossal ignorance and accepted me (against, I later found out, considerable well-merited opposition!).

His tact and patience were boundless: he lent instruments, books and music, and all the time, in the gentle, understated way of his, he not only taught but educated. The Early Music Department at Trinity (founded by Edgar, and the first in a London music college) was an exciting and a happy place. He introduced his students not only to the recorder, but also to viols, baroque flute and oboe, and all manner of renaissance winds – all using instruments from his personal collection. He invited me to play with him and Maria Boxall in the ‘Bressan Ensemble’ in which he played his original – and quite fabulous – Bressan recorder. Taking over from him when he retired from Trinity was a huge honour, but also a huge responsibility. As ever though, Edgar was helpful, generous, and a constant source of good advice.

Coming as he did so near the beginning of the Early Music revival, Edgar had an inexhaustible supply of anecdotes about his peers. He was rarely openly critical, but one learned to interpret his language, and to draw the required distinction between “dear old” Walter (Bergmann) or Kees (Otten) on the one hand and simply “old” Bob (Thurston) Dart or Staeps on the other!

I have been privileged to work with all three of the giants of the English recorder revival – Walter Bergmann, Carl Dolmetsch and Edgar. All three made deep impressions on me: Walter – passionate, opinionated, profoundly musical, and (thankfully!) failing to conceal his warmth and wit behind the facade of an immaculately dressed Herr Doktor; Carl – dapper, precise, flamboyant in performance and exotic. Edgar was different – self deprecating and modest, his scholarship and musicianship shone through in his teaching. His endless delight in the constant evolution of early music research and performance made him a unique guide and mentor. Crucially (and more, I think, than his two contemporaries and friends) he remained fascinated more by questions than by answers.

It is, however, the small things which recall him most vividly. Visiting him on a winter evening in Amersham, where the fire was kindled with wooden Schott descant recorders which had failed his rigorous quality control. His fluent, but somewhat Churchillian French when we taught together on the Anglo French Summer School. Finding ourselves locked out of the Arras campus of the same summer school after visiting a local bar, and watching nervously as Edgar shinned over a ten-foot gate with an ease that hinted at a misspent youth. His tales of army life in India, where he was a radio DJ, his christening Jean Henri’s poodles “les musichiens”, and having the wrong pair of glasses for the task in hand – always! And so much more. Dear old Edgar!

Philip Thorby

Edgar Hunt’s death is a loss not just to his very many friends, pupils and acquaintances and of course his family but to the entire recorder playing community in this country. In a career spanning more than 70 years, Edgar pioneered the use of the recorder in primary education. With his one time employer Messrs. Schott he sought out and imported an inexpensive recorder firstly in wood but later in plastic and made it available to generations of school children. Also largely forgotten is the fact that he almost single-handedly fought a campaign to keep chromatic ‘German’ fingering out of this country. Something which still plagues teachers and manufacturers on the continent.

As a person Edgar was simply the epitome of a well-tempered English gentleman. Patient, generous, modest, self-effacing and always utterly reliable. Nothing was ever too much trouble and any request for advice or help would always be offered in an informed and well-thought-out way without any thought of reward and of course in his uniquely beautifully copper-plate handwriting.

Others more qualified than I am will give an account of his teaching career at Trinity and elsewhere but it is as a teacher and a writer of tutors that he will most be remembered.

Edgar was a good personal friend. For years he and I shared the trip to Boston USA and the hospitality offered by Friedrich and Inge von Huene over the week-long Boston Early Music Festival. We stayed in their home and I have vivid memories of the post-concert parties when Edgar, glass of wine in hand showed off perhaps his greatest talent –reminiscing.

He last attended BEMF in June 2003 aged 93. Edgar refused to be talked out of going and unfortunately paid the price. After one afternoon’s recital he refused a lift offered to him and set off walking back to Brookline with the temperature at around 85 and the humidity as high as it could be. Edgar was dressed as always in his three-piece suit. He collapsed and ended up in hospital. I visited him every day as he steadily recovered.

Dear Edgar we shall all miss you.

Richard Wood.

I first met Edgar Hunt on April Ist 1939 when the recorder group from my Southampton grammar school came up to London and played to a meeting of the Society at the Art Workers’ Guild. I still have a vivid recollection of Edgar’s valiant and vain attempt to get the 50 tweedy amateurs assembled there to play in tune on a wildly incompatible collection of instruments. It may have been that very occasion that led to this passage in his editorial in the issue of The Recorder News for that period.

“Much harm is done to the recorder movement by the amateurishness of many of its keenest supporters. Musicians in general will not take the recorder seriously until recorder players behave as normal musicians. First of all there comes the matter of music stands – learn to manipulate them without pinching your fingers or getting in a muddle. Then when tuning, play your note and see whether it is sharper or flatter than the standard adopted and quickly adjust the instrument: some players continue to blow hopefully as if they expect the pitch to right itself!”

It is fascinating to follow the course of his involvement through the pages of The Recorder News which he and Carl Dolmetsch jointly edited. On the afternoon of May 7th 1938 fifty-three members of the Society and sixteen guests met, courtesy of Mr and Mrs Arnold Dolmetsch, at Jesses in Haslemere; toured the Dolmetsch workshops; repaired for tea to the Three Limes in the town and returned to combined playing at Jesses. At 6 pm the Chairman, Max Champion, announced that Mr Arnold Dolmetsch was to honour the gathering with his presence. After a spirited address the grand old man turned to Edgar and addressing him as one of his disciples presented him, on behalf of the members with a cheque for S,12.12s on the occasion of his forthcoming marriage to Miss Elizabeth Voss.

At the first summer school in July 1939 he had 19 players, several of them complete beginners and all but two playing only trebles. Would any teacher nowadays have the nerve or the stamina to run such a course single-handed for a week with the tiny repertoire of recorder music then available? The pupils apparently all enjoyed themselves hugely and at the end presented Edgar with an Eversharp propelling pencil.

Then came the war and Edgar was called up, but Gunner Hunt E. still managed to wangle leave to run summer schools at Downe House in 1940 and 1941. Wartime shortages however seem to have precluded the presentation of propelling pencils.

Theo Wyatt

Edgar retired from Schott about 30 years ago and, sadly, there are few currently active within the company who were here during his working life. Those that were will always be struck by his encyclopaedic knowledge – not restricted to musical topics only – and his thoughts and advice (never advanced without invitation) being unfailingly expressed with great kindness and courtesy.

As a company, of course, Schott is extremely proud of its association with Edgar over such a long period. In addition to his lasting contribution – with that of his colleague Walter Bergmann – to the Schott recorder catalogue, Edgar as a Schott employee was also responsible (during the 50s and early 60s) for overseeing the production of many scores in our general and contemporary music list –including major scores by Tippets and Goehr -which remain in print. For all his work at Schott -and for the memory of his unique personality – we remain extremely grateful.

Schott and Co.

Perhaps in conclusion I might be permitted to add my own memories of Edgar. I knew of him, of course, virtually from the time I took up the recorder, but it was not until I became editor of The Recorder Magazine that I came in contact with him – or more accurately, he contacted me. His support during the early period of my editorship was indispensable. The letters he wrote to me at that time, so full of information, and the articles he contributed, were a tremendous encouragement. What also comes to mind is his remarkable memory for detail. Edgar was involved in what was among the seminal events in the establishment of the recorder’s contemporary repertoire. On 17th June 1939, together with Carl Dolmetsch, he took part in a recital at a studio meeting of the London Contemporary Music Centre. Carl gave the first private performances of the Sonatinas by Lennox Berkeley and Stanley Bate, Edgar of the Sonatina by Peter Pope (that was dedicated to him) and a work by Christian Darnton, later withdrawn by the composer. It would have been in 1997 that I asked him about this recital and the Darnton piece in particular. His recollections were as if it had taken place only months rather than almost sixty years earlier! I have kept all the letters he wrote to me. Most were in reply to questions in connection with my research, but they always contained that bit extra -those fascinating details that he alone seemed able to supply, and which I will always value with gratitude and appreciation.

There is no doubt that Edgar’s vast contribution to the recorder will be appreciated and have an influence while the instrument continues to be played and enjoyed. However, the respect and esteem, but above all, the affection with which he will be remembered by all who came into contact with him will also remain as a testament to his unique character. There can be no more fitting tribute or memorial than this.

Andrew Mayes

Also see an obituary by Hélène La Rue, 2006. Edgar Hunt (1909-2006), Galpin Society Journal, vol. LIX, p. 288-291.